Death is Just Another Act, Believe Mexicans: That’s Why They Take Life with a Smile

The Day of the Dead in Mexico is not just a grand fiesta—it also forces a European to reflect on life and death. Is death the final stop? Shouldn’t we, perhaps, flirt with it instead of fearing it?

“I have two daughters, and I had a son too. He died when he was 22,” Alejandro, a taxi driver, confided during a ride through the festively decorated historic district of Coyoacán in southern Mexico City. The cheerful conversation suddenly grew heavy—mostly on my part. I fell silent and assumed a solemn expression. Sensing my thoughts, Alejandro burst into laughter as if to lighten the moment: “Life goes on. I know we’ll meet again. In Mictlán. One day, we’ll reunite in Mictlán!”

Mictlán. The Aztec afterlife. A mythical underworld where the souls of the deceased go after death, governed by Mictlantecuhtli and his wife Mictecacihuatl. Before standing in front of them, the dead must overcome nine challenging levels, and at the end of this arduous journey, they find eternal rest.

The name of this place, translated from the ancient Nahuatl language as "Land of the Dead," is on everyone’s lips in Mexico at the end of October. The streets and squares light up with vibrant orange-yellow cempasúchil flowers, which, according to legend, glow like lanterns guiding the dead back to our world. In bakeries and cafes, pan de muerto—"bread of the dead"—fills the windows, a staple for welcoming returning souls. Everything feels even more colorful and festive than usual in Mexico.

It’s Día de Muertos—the Days of the Dead. Days that, in my home Czech Republic, Central Europe, are shrouded in a somber web of grief, sorrow, and fear. But in Mexico, they are a reason to celebrate. The dead return briefly from Mictlán to greet us and remind us that life must be savored while it lasts.

Cempasúchil, the flower that guides the dead to the world of the living

The yellow-orange dome-shaped flower represented the sun's rays in Aztec culture. According to legend, it was supposed to illuminate the world of the dead and show the d…

It’s a significant marketing success that Halloween, with its fun costumes and antics, has made its way to the Czech Republic. Yet, as far as I can recall, our All Saints’ Days used to be somber—a time of decaying leaves, darkness at 5 PM, rain, and flickering red candle flames dancing like will-o’-the-wisps around graves no one dared approach after dark.

I loved it. It carried that Slavic gloom. It was eerie, mysterious, alien, and distant. As if saying: "Don’t come here. This is ours now, and you don’t belong." It scared me, as cemeteries are supposed to.

In Mexico, it’s the opposite. It’s as if they’re inviting you to a never-ending fiesta among the dead. "Come on in, it’s lively here!" they seem to say. On these nights, families and friends gather around the graves of loved ones, savoring the moments together. Some even spend the night there. There’s no reason to fear.

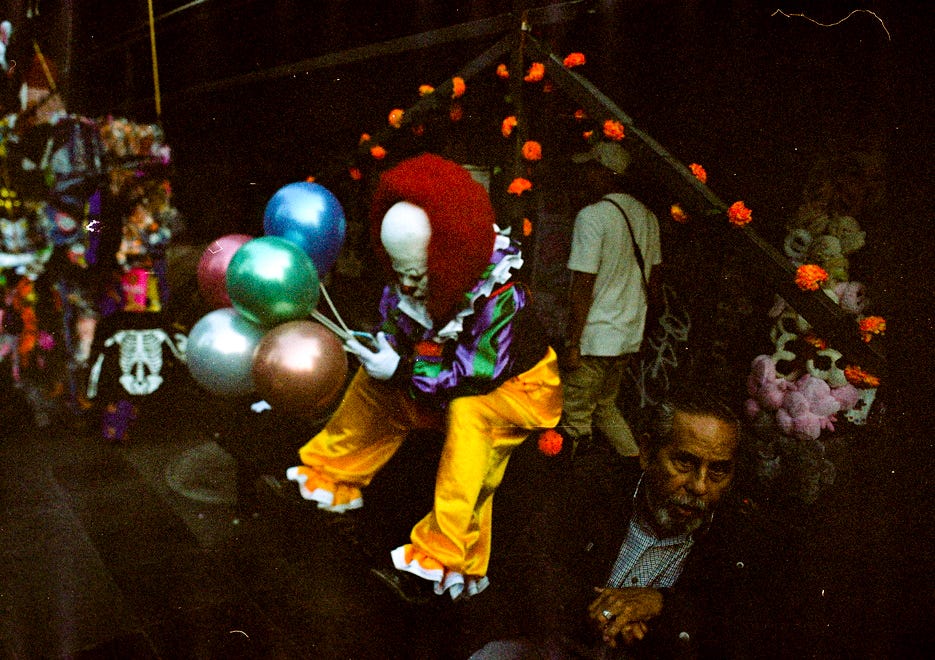

Starting mid-October, everything in Mexico revolves around these celebrations, peaking between the last day of the month and the night of November 2. During this time, the paths from Mictlán are most crowded, and the streets of Mexican cities and villages buzz with life. There are festivals everywhere, always with plenty of food, loud music, dancing, and festive attire.

People build ofrendas—colorful altars with offerings—in their homes, workplaces, or even in public spaces. These altars feature pan de muerto, sweets, perhaps a splash of alcohol, or anything the deceased loved in life. When Día de Muertos arrives, the festivities reach full swing. People feast, drink, sing, and reminisce. On November 1, the spirits of deceased children and pets are remembered; on November 2, the adult dead are honored.

In Mexican culture, life and death are not opposites but interconnected parts of existence. The ancient civilizations believed human life doesn’t end with death—it transitions to Mictlán, a place of peace and tranquility. This may explain why Mexicans seem so accepting of death.

In a country where many survive on just a few pesos a day, and where an average of four people are murdered every hour—those known to authorities, that is—people remain unshaken. They appear optimistic, grounded, and unconcerned with trivial matters. Sometimes, they seem unfazed even by the greatest tragedies.

About two years ago, I had breakfast with a middle-aged Mexican woman, a cleaner for wealthier compatriots. By European standards, she was merely surviving, not living. Yet, she radiated a healthy and balanced energy. Between bites, she casually recounted attending the funeral of a relative’s baby, describing the customs: selecting the coffin, baptizing the body, and dressing the infant. Her tone was so matter-of-fact, you’d think she was talking about what’s for dinner.

This isn’t to say Mexicans are cold-hearted cynics—they’re far from it. Instead, it reflects their approach to life: enjoy it, don’t dwell on it. As one Mexican friend often reminds me when I’m overwhelmed by responsibilities back home in the Czech Republic: "Life isn’t for overthinking—it’s for living."

Of course, it’s easier to say that in a country where you don’t spend half the year in fog and mud. In a country ruled by corrupt sirs, but at least they don't prey primarily on the least fortunate. In a country where you can always get food at a reasonable price, and if you can't, people share among themselves without talking. Here, most accept their modest lot, choosing to live simply rather than burn out in the rat race.

Beer and jo*nts and warm people: Santa Muerte's mass in the gangsta neighborhood

The first of November is the day of Santa Muerte, the patron saint of outcasts of all kinds. I couldn't miss the mass of her followers at the altar of Saint Death in the dreaded Tepito district of Ciudad de México.

And so they're dancing this tango with death. Norbert Frýd, Czech writer and diplomat, illustrated how Mexicans interact with death in his book Mexico is in America, recounting an incident at a bullfight:

"During a bullfight, a particularly wild animal was released into the arena. The crowd was furious and whistled because the experienced torero seemed unsure of how to handle it, perhaps even afraid. Then, out of the crowd, a 16-year-old boy jumped into the ring, almost landing on the bull. As soon as he regained his balance, he began teasing the animal with a red cloth. The bull charged him, but the boy deftly dodged, following the torero’s art. The crowd screamed in excitement...

Nothing happened, an espontáneo,” my Mexican friends shrugged when I later asked them about it. “An enthusiast, it got to him and he jumped into the arena—this is a common feature at many fights."

"But the bull could’ve killed him?" I asked.

"Sure, and sometimes it does happen. If it wasn’t dangerous, the boy wouldn’t have done it..."

After reading this passage, I realized that this is what attracts me to Mexico—the life on the edge, flowing from their indifferent attitude toward danger and death. And that much greater passion and love with which people here approach life itself, no matter how hard it is.

It does, however, have its caveat. I immediately wondered if this passion and lack of fear might also be fueling the violence happening here. I did some research and found that scientific studies have already been conducted on this topic. For example, local anthropologist Claudio Lomnitz speculates in his book Death and the Idea of Mexico that Mexicans’ tendency not to shy away from death may be linked to their willingness to confront the violent aspects of life. According to him, the long-standing tolerance of death could create a culture in which violence is partially accepted. As we sadly see today.

This is further supported by the ubiquitous and especially in recent days increasingly popular narcoculture, which celebrates aspects of the gangster lifestyle, as we know it, for example, from Netflix. Mexican culture expert José Luis González, in his text La naturalización de la muerte en México (The Naturalization of Death in Mexico), points out that in its depiction in pop culture, violence and death are often either glorified or accepted as a common phenomenon.

In his book The Labyrinth of Solitude, Octavio Paz writes about Mexicans, saying that for them “living means risking and loving every moment,” a perspective that can also be attributed to their acceptance of mortality. And yes, we could take an example from that—living wildly, uncompromisingly, “here and now.”

And to conclude, I would like to remind you of the words of director Guillermo del Toro. When asked how he manages to explore the darkest aspects of life in his often harrowing works, while still being such a pleasant and kind person, he answered: “Because I am Mexican. No one loves life more than we do—because we are aware of death. The preciousness of life stands side by side with that one place we all head toward. We’ve all boarded a train with the final destination Death. So in that train, we will live! There will be beauty, love, and freedom.”